Vulnerable groups vote and participate in politics less than their white, affluent counterparts. Here’s what some organizations are doing about it.

Ever since her early teens, Amina Khalique had been interested in politics. But because she rarely saw people from her background — a young Bangladeshi muslim — in local or national politics, she assumed it wasn’t for her.

That perception changed when Gabriela Santiago-Romero came to her high school to tell students about Girls Making Change, a political leadership fellowship for high school girls of color. Though the deadline was fast approaching, Khalique applied and was accepted to be one of a dozen girls enrolled in the program.

She’s only 18, but Khalique already knows the experience was life-changing. “It gave me a voice, showed me I can be a leader, and gave me so many more opportunities than I could ever imagine,” she says.

Over 10 weeks in the summer, the young women participate in leadership workshops, organize a community impact event, and shadow a Michigan legislator, including now-State Senator Stephanie Chang, who started the program in 2016.

Khalique, who is currently a student at Wayne State University majoring in political science, became a program assistant for Girls Making Change last year. She’s organized a couple rallies since the fellowship and one day hopes to run for office herself. “That’s mostly because of Girls Making Change,” she says.

And that’s exactly the goal — the program hopes to create a pipeline of political leadership in Metro Detroit.

“If we elected people who actually understood the community, we might have more creative solutions,” Santiago-Romero says. “White men who are able-bodied, straight, affluent, have a wonderful family — congratulations, you’re fine. But you might not understand that there are people in the community who don’t have water, can’t get to school, have trouble making ends meet. If it’s a nonexistent reality for you, then you won’t fight for it.”

Historically disenfranchised communities — the poor, immigrants, people of color — often struggle to be civically engaged. Sometimes that’s because, like Khalique, they don’t see themselves represented in politics. Other times it’s through active voter suppression or because the process is intimidating, confusing, or disillusioning.

But those trends have been changing in recent elections. And the actions of some organizations to engage these groups may shift the scales even more.

The numbers

The simplest metric for measuring civic engagement is voter turnout. And in almost every American election, vulnerable groups vote with less frequency than their white, affluent counterparts.

Minority voter turnout has consistently lagged behind white voter turnout. In the 2016 election in Michigan, for example, 66.5 percent of the white population voted, whereas 61 percent of the black and 36 percent of the Hispanic population did.

In the 2010 election, only 28 percent of eligible voters who make under $20,000 a year cast a ballot, and 39 percent for those who make between $20,000 and $50,000. But turnout shoots up to 60 percent for those who made more than $100,000.

Turnout also increases with educational achievement. In the 2014 election in Michigan, only 21 percent of those without a high school diploma cast a ballot.

The reasons for these outcomes are many. In some states, like Wisconsin, Georgia, and North Carolina, there have been active efforts to disenfranchise voters through policies that primarily affect vulnerable groups, like Voter ID requirements and insufficient polling stations. This was made possible in part when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down parts of the Voting Rights Act in 2013, allowing southern states to enact policies that would have otherwise been under review and potentially overturned.

Gerrymandering, the practice of packing districts during a census year to make elections less competitive, is common across America. But it’s especially egregious in Michigan, which has been described as having “some of the most partisan maps in the nation.” Noncompetitive races increase voter apathy and suppress turnout.

But there are other, more subtle ways vulnerable groups are disenfranchised. In Detroit in 2016, widespread voting machine failures invalidated thousands of ballots. Issues at polling places sow distrust in the political system and make people question whether their vote matters.

The same goes for excessively long lines at polling stations, unclear requirements or deadlines for registration, cases of unsent absentee ballots — all of which affect minorities at considerably higher rates.

A Caltech/MIT survey conducted on non-voters found that “white citizens who abstain from voting do so primarily by choice, while the majority of minority non-voters face problems along the way.”

These numbers are reflected in other areas of the political process. Money to candidates, campaigns, and political action committees overwhelmingly comes from the wealthy. An article in The Atlantic titled, “Why do minorities vote less?“, posited that “low-income people lack funding to effectively advocate” for their needs and are under-represented as a result.

It continued, “Just 2 percent of Americans at the bottom of the income and education ladder attend campaign meetings and rallies or conduct campaign work, compared to 14 percent of people at the top — a factor of seven to one. When it comes to selecting candidates and funding their campaigns, 2 percent of all Americans give money in presidential elections and less than half of 1 percent provide the lion’s share.”

That results in lower representation in political bodies and fewer policies that reflect their interests. Prior to the 2016 election, there were only eight women of color out of 148 in the Michigan Legislature, almost all of whom were from Detroit.

Solutions on the way

More representation is not just about combating apathy among underrepresented groups — it has a direct effect on policy.

“Having greater representation lends itself to more voices that bring up issues that wouldn’t otherwise be raised,” says State Senator Stephanie Chang says. She cites the example of Detroit City Councilmember Raquel Castañeda-López who championed Municipal IDs in Detroit, which are especially important to immigrants and those from her community in Southwest Detroit.

“Having more women, people of color, immigrants — all of those things are about creating better policy,” she adds.

Chang, who became the first Asian-American woman elected to Michigan’s Legislature in 2014, started Girls Making Change in part because there was little precedent for a person of her background to run. But, she says, she was inspired by politicians like Castañeda-López and Rashida Tlaib, women of color organizers from Detroit, who successfully made the jump into politics.

Because of her belief that constituencies must dictate policy, Chang is often present at events in her district, a long strip that runs along the Detroit River from the eastside of Detroit and parts of downriver like Trenton and Grosse Ile. She holds regular coffee hours, where constituents can speak to her in person, and town halls every other month on issues like voting rights.

Chang had been a state representative since 2014 before the most recent election, where she rode a wave of enthusiasm from minority voters in local and national elections. Last year’s election had the highest turnout for a midterm election in decades. As a result, political bodies have become more diverse.

In 2018, Michigan voters election women to the highest offices in the state — governor, secretary of state, and attorney general — and the number of women in the legislature grew by 15 to 53.

41 new women were elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, two of whom are the first Muslim women elected to Congress. 2016 saw the first Thai-American (Tammy Duckworth) and Latina (Catherine Cortez Masto) elected.

It’s clear that people of all races, classes, and backgrounds are motivated to vote — now it’s a matter of getting them registered, informed, and engaged.

Michigan voters helped the cause by passing a pair of ballot initiatives in 2018 designed to increase election turnout and fairness. Proposal 2 combats gerrymandering by having a 13-member independent citizens’ redistricting commission approve new district maps. Proposal 3 institutes a bevy of voter-friendly policies, like making it much easier to register and to vote absentee.

CitizenDetroit is also doing its part. Co-founded by former Detroit City Councilmember Sheila Cockrel, the voter education group organizes all kinds of events, from candidate forums and debate watch parties to bar trivia nights centered around a political theme.

These kinds of activities are in pursuit of its main goal, which is, according to Cockrel, “to provide factual information that you distill with your personal values to help you decide what your position is on policies and what candidates meet your vision.”

To that end, CitizenDetroit created a website, informdetroit.org, that provides information and a three-minute statement from practically every political candidate in a local or statewide election. “If we could find your email address, we reached out to you,” Cockrel says.

It also puts together workbooks on select topics and ballot proposals. Its workbook on the Detroit Charter Revision, for example, had information on the history of the Detroit charter, its mandate, the positions and background of those running to be on the commission, as well as contact information and other resources.

The organization takes no positions and doesn’t endorse candidates. “We’re rigorously nonpartisan,” Cockrel says. “We’re not gonna come down the mountain with tablets. Rather, let’s start with an agreement about facts.”

It’s also rigorously pro-voter. Starting this year, Cockrel says the organization wants to reach more voters “who don’t believe that voting impacts their lives and that it doesn’t matter who’s in power.” It’s piloting a number of strategies to do so, including using voter databases to reach out to registered non-voters, as well as promoting participation in the 2020 Census.

Simply registering to vote is an issue that especially impacts immigrant populations. First-generation U.S. citizens register and then vote at a much lower rate — whereas the descendants of immigrants do so at higher rates — than the rest of the population.

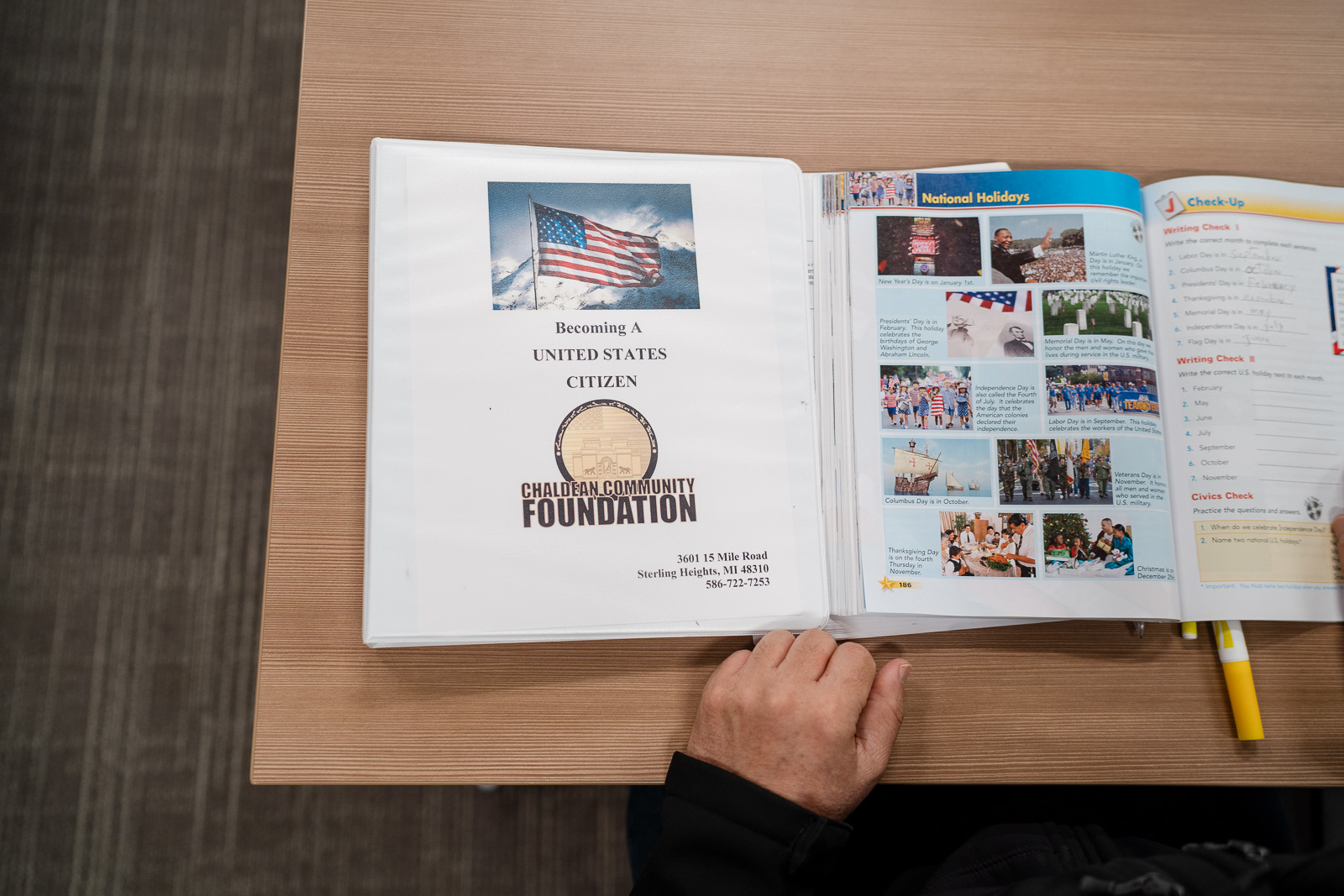

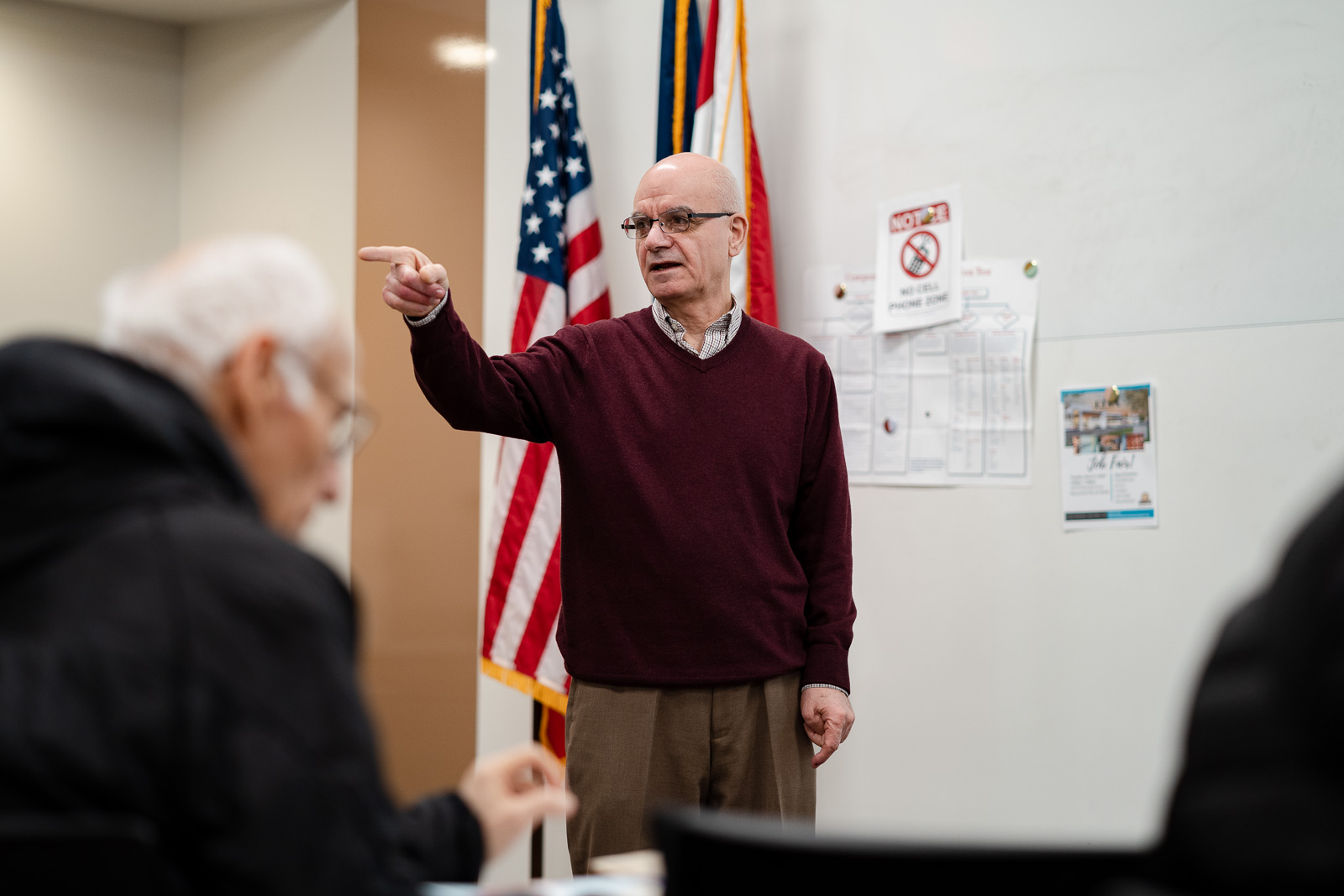

Language barriers and a lack of familiarity with the process are the main reasons why. And organizations like the Chaldean Community Foundation are working to overcome these obstacles.

Chaldeans are Aramaic-speaking, Eastern Rite Catholics indigenous to Iraq. They migrated in large numbers to Metro Detroit during the Gulf War in Iraq. Many continue to flee persecution in the Middle East and settle here. Of the 31,000 individuals the Chaldean Community Foundation serviced in 2018, 80 percent were Chaldean, but it doesn’t turn away anyone with a genuine need.

Those who come to the foundation seek help for a variety of issues — citizenship, language competency, employment, health. Sometimes they arrive for one reason, like finding a job, but come to realize other barriers, like PTSD, need to be addressed first.

“We try to serve the whole person — the mind, body, and soul — in one place,” says Paul Jonna, COO of the Chaldean Community Foundation. “So that they can get a job and stand on own their own two feet.”

Taking care of these fundamental issues is also a necessary prerequisite to civic engagement — joblessness, poverty, poor health, and low educational attainment are all compounding factors that make someone less likely to vote.

Another prerequisite to voting is actually being a citizen. That’s why the foundation offers a citizenship class that covers American civics, American history, English, and everything required in an application for naturalization. The class also teaches students the basics of voting, using a mock ballot to demonstrate. Last year, the foundation filed 4,192 immigration applications.

Once they’re citizens, the foundation helps them register. In 2017, it launched a voter drive, Hey U Vote, to make the registration and absentee voting process as clear as possible.

“Our goal is to get them to understand how system works, that they have the right to vote, and then how they can vote,” Jonna says. “They’re very eager to be part of it.”

The importance of voting, especially in the Chaldean community, came into sharper focus when around 100 Iraqi-Americans were detained and 1,400 faced deportation because of President Trump’s anti-immigration policies.

“There’s definitely been a bigger push towards citizenship,” says Leila Kello, director of development for the Chaldean Community Foundation. “Prior to the last election, some asked ‘What do I need to become citizen for?’ Now, they get it.”

This article was made possible through a grant from the Solutions Journalism Network as part of its “Renewing Democracy” initiative, which encourages reporting about how people and institutions are attempting to reinvigorate democracy in communities across the country.

On March 27 from 6 to 8 p.m., Model D will be co-hosting a listening and strategy session with CitizenDetroit to develop more solutions to the region’s most pressing civic engagement issues. Food and drink will be provided.

RSVP for the free event here.

All photos, except where mentioned, by Nick Hagen.