Finding Detroit’s place in the Black country music canon

The “who owns country music” debate has some talking points in Detroit.

Southeast Michigan is both a likely and unlikely place for country music’s earliest beginnings. The region does not claim the cowboy past present in Tennessee, where Nashville is the nucleus of the country music industry, nor Texas, whose native daughter Beyonce is the more recent cause for commotion. But the area’s thoroughly American industrial and manufacturing industries and the people who work within them, telling tall tales of drinking too much, making bad decisions and strings of lovers, do allow Detroiters to claim some parts of the genre’s rise to prominence.

Alice Randall does not want us to forget Black Detroiters’ place in country. The writer, educator and Detroit native — you may remember her 2020 novel, “Black Bottom Saints,” set in the historic neighborhood of the same name — is gearing up to release her newest book, “My Black Country: A Journey Through Country Music’s Black Past, Present, and Future” in April. The book travels between Randall’s accounts as one of Nashville’s few Black songwriters (and the first Black woman to co-write a No. 1 song on Billboard’s country chart) and a full accounting of the largely unsung Black figures that helped shape the genre.

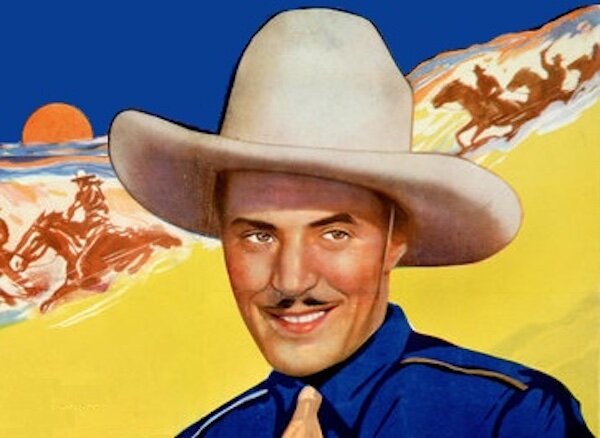

One of those figures is Herb Jeffries, a Detroit-born singer and actor who was a pioneer in Hollywood’s early Westerns. “He didn’t invent the genre, but he created the largest numbers of works in the genre of the Black singing cowboy western,” Randall says.

“My mother was Irish, my father was Sicilian, and one of my great-grandparents was Ethiopian,” Jeffries said by way of an obituary from the Los Angeles Times. “So I’m an Italian-looking mongrel with a percentage of Ethiopian blood, which enabled me to get work with black orchestras.”

Jeffries learned to ride a horse on his grandfather’s farm in Northern Michigan. Initially singing jazz and swing with Duke Ellington’s orchestra, Jeffries returned to the ranch when conceived the idea of an all-black western musical. He starred in “Harlem on the Prairie” in 1937, then followed up with four more in the genre: “Two-Gun Man From Harlem” (1938), “Rhythm Rodeo” (1938), “The Bronze Buckaroo” (1939), and “Harlem Rides the Range” (1939).

“To say I was the first Black singing cowboy on the face of this earth is a great satisfaction,” he said before his death at age 100 in 2014.

But despite Jeffries’ roles as the hero in his flicks, historians noted that the cowboy films did not win over Black audiences.

“He was never quite popular with blacks in this arena, because many were not sure he was black: His fair skin, wavy black hair and good looks also confused white audiences, who were not sure of his ethnicity. This ambivalence seemed to dog Jeffries throughout his career, despite the fact that he possessed one of the most beautiful baritone voices in popular music,” Bob Perkins, a one-time voice heard on WGPR, writes.

Perhaps Jeffries was ahead of his time, or perhaps he’d be the beginning of a long-running conversation of what exactly a country music balladeer should look like. Randall notes that Beyonce is far from the first Black artist to wade into country music, and further from the first to raise skepticism.

“My favorite line in my book…is ‘Somebody once told me to go back. Go back to where I came from. I said, if they knew where I came from, they wouldn’t have told me that,'” Randall says.

Randall points out two — of many — defining turns in her upbringing that led her on a path to Nashville, where she co-wrote “XXX’s and OOO’s,” the aforementioned No. 1, for Trisha Yearwood. One was being in the audience as a young girl at The Supremes’ stand at the Copacabana nightclub in New York City. The trio was one of the first Black acts to play the then-integrating club, and the show was released as a live album, “The Supremes at the Copa.” Included in the set is “Queen of the House,” the female answer to the folksy traveling-man anthem “King of the Road.”

The second is when she wrote her first country song, “in a cherry tree by the John C. Lodge.” Randall drew inspiration for the tune, “Don’t Go in that B-A-R,” from her father that would frequent a bar in town with a neon sign reading “B-A-R.” Her father would later inspire other lyrics.

“I would look sad some days, [and my father] said, ‘What’s wrong, little girl?’” And then he’d joke about putting out a hit.

“He’d say, ‘it only takes $40 to get anyone killed. $40 to nail to the dope house door will get anyone killed. I got $40. It might take $100 in the morning, but by evening, there’s always a junkie wants a fix,’” Randall recollects. “That’s the country song I come from.”

“I am a very nonviolent person, but I come from that kind of defiance where fathers would talk to their little girls with crazy stories about the difference between what $100 means in the morning and in the afternoon,” she adds. “So I love the grit and I love the grace. And I think, all through it, joy is radical, and so is Black storytelling. What was most powerful about that story is my father noticed when my head was hanging low, and what he was saying in the metaphor, which is what taught me to write country songs. That was a metaphor. ‘Whatever it takes to get your head up, I have it.’ We have it between us.”