Guest column: What Michigan can learn from Bolivia’s water crisis

You might wonder why a little country in South America should matter to Michiganders. Valerie Vande Panne went to Bolivia to learn about how citizens asserted control over their water systems, and how Michiganders could do the same.

You might wonder what that has to do with Michigan—or why a little country in the heart of South America should matter to Michiganders today.

The reason is simple: The Bolivian people faced corporate water control, demanded, and fought for, their water. And they won.

In 1999, the Bolivian city of Cochabamba’s water system was privatized. Water rates skyrocketed 200 percent as the nation struggled to pay off debt and keep it’s water system profitable. In rural areas surrounding the city, citizens had in many cases constructed their own systems of irrigation and water transport, some of which were used to capture rainwater. These too became privatized. Suddenly, the very systems the people themselves built were owned by Aguas del Tunari, an international consortium whose major shareholder was San Francisco-based Bechtel. It seemed the corporation was charging people to use the rain.

By January of 2000, protests had begun. The Bolivian government refused to lower water rates. The people stopped paying their bills, continuing to protest and demonstrate. The government brought in more police forces. In just two days, 175 protesters were wounded. More people came to Cochabamba to protest, blocking major roads and highways. The military then stepped up their control. A teenager was killed by police. The protests grew.

Finally, the contract with Aguas del Tunari was broken and water was restored to the public.

The story, as romantic as it seems—protesters fight for and win the right to their water—doesn’t end there. In fact, it was only the beginning.

Today in Flint, the city is looking at a price tag in the hundreds of millions of dollars to replace its contaminated, eroded pipes. Meanwhile, 100,000 people continue to drink, bathe, and wash their clothing and dishes in bottled water, as they have for over two years. Celebrities make a show of donating water to Flint. And while it’s no longer hot national news, the people there are still living in a way that, for most Americans, is unconscionable.

Meanwhile in Detroit, 70,000 households have had their water shut off. Many families take buckets to the nearest functioning fire hydrant to fill up. The city has tied back water bills—now among the highest in the nation, in a city with a poverty rate of at least 40 percent—to property tax liens, and will seize the home of those too far behind. Again, an unconscionable circumstance.

In the wake of water crises never before seen in Michigan, or even the United States, we should look at what Bolivia is doing with its water.

There, in a nation with the fastest growing economy in Latin America, the country is facing ongoing crises caused by climate change and lack of resources and infrastructure. Yes, they kicked out a multi-national water company. But the people of Bolivia are now making coordinated, ongoing efforts to protect and secure safe water so it doesn’t happen again.

Again that sounds romantic. In reality, it’s a lot of hard work.

If you ask people about the water, they will proudly tell you of the well or water system they are a part of—water systems, more often than not, they had a hand in building themselves and a say in the construction plans. Communities meet regularly to discuss the water—where it comes from, how to protect that source, and how to transport it. They network, share strategies, divvy up tasks, and do their own research. They share their findings and collaborate on best actions and practices. These aren’t unions, or hierarchical organizations, and they encompass the lower, middle, and upper classes. And they aren’t working against the public utility—they work with, and in many ways are the utility.

If you have a conversation with an average Bolivian about water, they have a much more sophisticated understanding of it than the average Michigander. Bolivians overwhelmingly consider water a human right—this fact, vigorously contended in Michigan, isn’t even up for debate there.

“You can live without a roof over your head. You can live without food everyday. You can live without electricity. You absolutely can not live without water,” says Oscar Campinini, project director at CEDIB (Documentation and Information Center of Bolivia).

From there, conversations get deeper, and there are more questions than answers. Indeed, Bolivia isn’t a solution to the water crisis in Michigan. But those questions—questions asked by the people themselves—are where we should start.

For example, in a diverse community, with diverse economic interests, how do you make sure the poorest among you has water? The elderly? The disabled? How do you make sure they are provided for? Certainly, a family of five with multiple family members working has more access to resources than an elderly man living alone, or a single mother struggling with many young children.

Here’s another difference that might be a sticking point at home: In Bolivia, the wealthy understand that water is a human right, too. And they pay more, so that the less fortunate don’t go without it.

Are wealthy Michiganders willing to pay more to ensure a just water system?

It isn’t like people are all that different in Bolivia. They struggle with the toxic impact of mining, just as we do with industry.

Bolivians don’t want to watch members of their community suffer for lack of water—it’s a human right, after all. And there is no righteousness in telling people to get a job. There is an acceptance that there is no job for them to get, that the government will not and cannot provide everything that they need. And there is an understanding that they must take matters into their own hands.

Imagine that: Taking our water into our own hands, for the benefit of everyone. Can we do that in Michigan? What would that even look like for us?

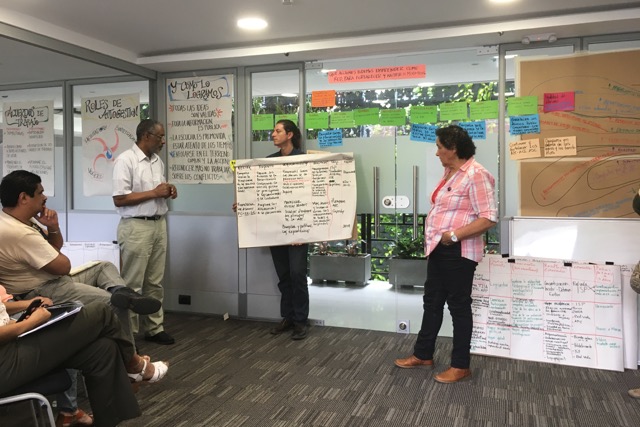

On a recent trip to Bolivia, I explored the nation and met with leaders on water issues, searching for answers. At each of these meetings, I asked what was being done to get water to the people. In response I received more questions than answers—any of which would be wise to ask ourselves in Michigan.

“How can we find a way to balance the state and the community participation in water systems?” says Marcela Olivera of Food and Water Watch. “How can people participate more in the issues that effect the democratization of water systems? How can the public work with the water?”

These questions aren’t easily answered, especially when you have other interests—including mining companies—involved.

Too often, says Olivera, the World Bank and other international development organizations see water as a tech problem, not a cultural one. “How can we make policies that take into consideration the way societies have to organize themselves?”

Stefano Archidiancono works in Cochabamba for the Italian CeVI (Center of International Voluntary Service). He speaks of the importance of rainwater collection by communities and families, with water tanks near homes or on rooftops. In the context of water scarcity, he says the most accessible resource is rainwater. It allows a community to be more resilient if there is a water crisis.

“Even in the city, every building should have rainwater collection,” he says, “even if the water is only to flush the toilet.”

Archidiancono also talks about how the communities around Cochabamba build their own water systems and their own wells, sometimes even using converted car engines to pump the water from the ground, and letting gravity move the water through a pipe.

“If you can manage your own water, you have political power,” he says.

In this part of Bolivia, Archidiancono is blunt about what drives the people. “If it comes from need, I dig my own well or I die,” he says. “Afterwards, they have to organize for solutions. It’s the basis of life itself. As a society, we can have a say on water and on other things as well. This is where we start.”

Says Campinini, “We have more questions than answers. Who has the water? The people or the state? What can we do better? What is the solution? If all the people participate in the decisions, it’s better for everyone.”

A community, he says, can consider the problems of the very poor, the infirmed, the elderly—the problems that some can pay more than others, and how to fairly scale that.

“Together we can ask these questions,” says Campinini. “If it was private or with the state or by law it becomes political and the questions can’t be answered that way. It’s a public model, but at the same time, a social model, and it’s harder for a big company to consider these things.”

“Who is responsible for the water? The state or the people?” he continues. “It’s better when the people take it but that also presents problems. The water is for everyone, but the state can’t leave its responsibility.”

Community participation and control of the water is never simple, according to Campinini. “The most difficult part is the social participation and mobilization of the people to have the conscience and motivation to participate. How do you get the people to think, to read, and participate? How do you foster the collective participation of the people with different interests?”

Campanini tells a story of retired engineers getting involved—a group of professionals and intellectuals and environmentalists working together to build a system to transport water and protect park land at the same time.

“You can take different interests and put them together to fight for the water. Together.”

Can we do that in Michigan?