Two community benefits ordinances in Detroit set for ballot battle

Two bills on this year's ballot could establish a community benefits ordinance in Detroit. Nina Ignaczak delves into what that might mean for the city and the differences between the two.

When Marvis Cofield first heard of auto supplier Flex-N-Gate’s plans to invest $95 million in a new auto parts manufacturing plant on a 30-acre vacant lot near his neighborhood, he approached the news with some trepidation.

“I hoped that it’s not once again a business that comes in, we hear about it, and the next day they’re up and running without any input from us, the neighborhood community organization and community block clubs and the neighbors themselves,” says Cofield.

It’s something Cofield, C.E.O of Alkebu-lan Village, a youth development organization located in Detroit’s near east side, has seen happen before. The neighborhood sorely needs the new well paying manufacturing jobs promised by Flex-N-Gate, which is receiving a $3.5 million grant from the Michigan Strategic Fund and expected to receive city incentives as well.

But Cofield also wants assurances that the net impact of the project will be a benefit to the community. That includes things like access to the new jobs, affordable housing, and protection from pollution and noise.

The idea that members of a community should have some say in how development happens in their neighborhoods is at the heart of a movement to establish a Community Benefits Ordinance in Detroit.

It’s not a new idea. The movement first got underway in the 1990s with the development of the Staples Center in Los Angeles, home to NHL’s Los Angeles Kings, among other professional sports franchises. In 2001, activists negotiated a private contract with the developers of the project that spelled out how the developers would confer benefits to the community. Those benefits included provisions for parks and recreation, prevailing wages, training and hiring of the low-income residents, and affordable parking. In exchange for these benefits, the activists agreed to publicly support the project.

Since then, dozens of project-based community benefits agreements have been established in New York City, Oakland, Denver, and other cities across the country. They’ve secured everything from local hiring standards and affordable housing to support of a local grocery store and exclusion of big box retailers with track records of poor labor practices.

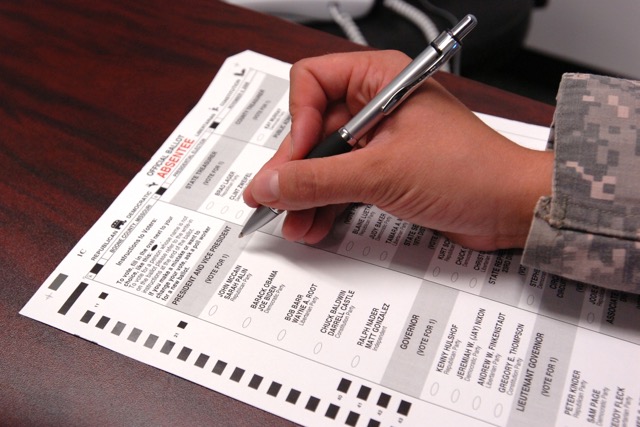

On their ballots this November, Detroiters will be asked to vote on two options to establish a community benefits ordinance in the city. If one of the options passes, Detroit will be the first city in the nation to establish a such an ordinance.

“It’s the first ordinance requiring the host community engagement process,” says John Goldstein, an independent consultant who works on CBAs. “There are a number of cities that have legislated standards that apply to all development projects. But this would be the first to require a process for community input “

The first proposal was drafted by the Sugar Law Center and driven by a petition from the grassroots community coalition Rise Together Detroit, whose member organizations include Equitable Detroit Coalition, Detroit People’s Platform and others. It’s commonly referred to as “Proposal A” or the “Sugar Law Bill.”

The second is put forth by Detroit City Councilman Scott Benson, and commonly referred to as “Proposal B” or the “Benson Bill.”

Developer Richard Hosey, whose projects include the Kirby Lofts in Midtown, sees a clear need for a community benefits ordinance in the city.

“Detroit is a city of people really excited about living here,” he says. “I really want that to continue, but I also want the actual benefits. Within the current population you have people who are already trained or easily trainable to do many jobs. And so getting this right is so important.”

Mildred Hunt Robbins, a community activist with the West Grand Boulevard Collaborative, sees the process as having as much benefit for developers as for the community.

“Developers are not taking advantage of local knowledge,” she says. “My primary issue is that there’s a great benefit, not to communities, but to developers to talk to us to get the benefit of our local knowledge and expertise that is resident in the community.”

VIEW THE DETAILS OF EACH BALLOT PROPOSAL >>>>

Two bills, two paths

Rashida Tlaib, who helped draft Proposal A, sees a need for such an ordinance on a daily basis.

“As I’m taking my son to school in the morning, there’s a homemade cover where people wait for the bus,” she says. “Somebody erected a wood and metal piece on top. These are things Detroit residents could be getting but for the tax breaks going to developers.”

Detroit City Councilman Scott Benson, who sponsored the competing proposal, also sees a need.

“The city needs to protect the community,” he says, “Oftentimes we do large projects, like the arena, where the community’s voices aren’t really heard.”

One of the criticisms of the CBA concept is that it might place a chilling effect on development. Hosey sees Proposal B as providing more security for potential developers.

“The intent is there [in Proposal A] but all the logistics of implementing it are missing,” he says. “In business whenever you’re trying to see if you’re going to take a risk, you need a enough certainty that a project can get to completion. I think the Sugar Law bill was designed with the idea of how wonderful things could be without considering all the places where it could go wrong.”

Benson sees the Sugar Law Bill as going too far in cutting the city out of the process and not enough to ensure that Detroiters’ voices are heard.

“[Proposal B] has a very prescriptive process; we have a timeline that needs to be followed and we have a selection process that guarantees the community’s voice will be at the table,” he says. Benson also views the higher threshold to trigger the CBA process as more in keeping with what has been successful in CBAs in other places.

“We looked at other cities—Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York City, and Pittsburgh. In all these places you see that CBAs are always done for $200-$300 million catalyst-sized projects, just because of the energy and efforts that it takes actually negotiate a CBA,” he says. “The $15 million dollar level [proposed by the Sugar Law bill] isn’t done anywhere on the planet earth.

Tlaib, on the other hand, believes the threshold must be lower to assure community access to the process.

“[The $75 million dollar threshold proposed in the Benson Bill] is just not reachable,” she says. “It wouldn’t apply to many future projects, which means we don’t get access to that table.”

Tlaib sees Proposal B, which was introduced after Proposal A got enough signatures to be placed on the ballot, as an effort on the part of city administration to confuse voters.

“The administration was surprised that we successfully collected enough signatures,” says Tlaib. “I think they underestimated the huge desire of Detroiters to change the rules of how developers do business.”

In her view, Proposal A is the stronger of the two measures because it’s led by community members and requires a legally binding agreement with citizens themselves, not the city.

“Proposal A is the true community benefits agreement,” she says. “[Proposal B] requires one meeting. The city development director gets to decide what to implement, and what not to implement.”

Benson points out that Proposal B will utilize city resources on behalf of the community.

“The enforcement side will be done by the City of Detroit; the Office of Human Rights, the Law Department, Corporation Counsel—those entities actually have the ability to enforce,” he says. “Enforcements are done by the city to ensure that the community’s concerns are addressed, and City Council maintains the role of being the ultimate arbiter in a situation where they rescind, if need be, any development incentive that may have been granted on the project.”

Benson points to the Flex-N-Gate project as an example where a city-initiated engagement between a community and developer resulted in a mutually beneficial agreement.

“That’s a situation where the community residents came to the table, supported by City Council, and negotiated directly with Flex-N-Gate on what kind of benefits they receive,” he says.

Marvis Cofield participated in those negotiations.

“We had a big town hall meeting where close to 200 people showed up and we talked about who we were and Flex-N-Gate had some of their directors, human services, human resource department,” he says.

The group hammered out an agreement on issues like facility safety, security, employment opportunity, training for neighborhood residents, and examining traffic patterns to protect the environment and safety of the community.

Cofield will be voting for Proposal B.

“I’m with Scott Benson because I saw it work, I was a part of it,” he says. “At the end of the day, city council and the executive branch were voted for by us. Their allegiance, their commitment should be to us. Whoever they want to bring into the city, they have to come to us and let us know in advance, as opposed to after the fact. I think it’s a win-win situation.”