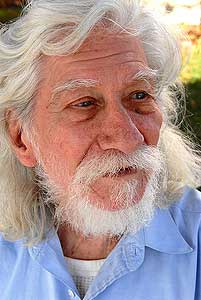

Model D-troiter: Pablo Davis

He charmed artist Frida Kahlo and rubbed elbows with actresses and dignitaries. At 90 and still charming as ever, Detroit’s Pablo Davis remains an activist, artist and great story teller.

For a 90-year old guy, Pablo Davis gets around pretty good. At least, that’s my first thought after meeting him. My second is that the twinkle in his eyes speaks of mischief, humor and above all, great stories.

I asked to meet with Davis in order to talk with him about the work for has done and continues to do for the elderly in Southwest Detroit. But it is hard to stay on such a narrow topic when the artist and activist I am sitting next to has had such a fantastic life — there are scores of movies and books based on individuals much less fascinating.

Davis is perhaps best-known as the last living artist who assisted on Diego Rivera’s “Detroit Industry” murals at the DIA. He was only 16 when, as the story goes, he charmed Frida Kahlo into an invitation into the museum where her husband, Rivera was working.

Davis is perhaps best-known as the last living artist who assisted on Diego Rivera’s “Detroit Industry” murals at the DIA. He was only 16 when, as the story goes, he charmed Frida Kahlo into an invitation into the museum where her husband, Rivera was working.

Davis was born Paul Kleinbordt in 1916 to Jewish immigrant parents in Philadelphia. He became a Communist and, after his Rivera-ful Detroit adventure, moved back to Philly then onto Spain—which is where he met Picasso—and then France—where he lived and worked with Picasso.

After being imprisoned in Denver, where he had immersed himself in the plight of Mexican-American migrant workers, he changed his name and moved back to Detroit. Over the years, Davis has painted portraits of luminaries such as Katharine Hepburn and Marilyn Monroe and politicians like Michigan Gov. John Swainson. His murals can be seen around Southwest Detroit and even Downtown, where his Mayan-inspired sculpted relief panels enliven the otherwise drab Comerica Building at Fort and Cass.

Davis remains impossibly inspired, still painting — one of the first things he said to me was, “I have 500 canvases left to paint!” — still advocating, still teaching. At his age, his AARP membership is nearing gold status, but that doesn’t keep him from working with fellow seniors, many whom have not enjoyed a life full of such success and excitement.

Davis remains impossibly inspired, still painting — one of the first things he said to me was, “I have 500 canvases left to paint!” — still advocating, still teaching. At his age, his AARP membership is nearing gold status, but that doesn’t keep him from working with fellow seniors, many whom have not enjoyed a life full of such success and excitement.

He first became involved in the lives of senior citizens in Southwest Detroit through an organization called Project SAVE (Seek and Visit the Elderly) in the early 1980s. Davis was struck by the plight of what he terms “the leftover generation.” Many whom he visited were living in relative isolation in homes that they had built themselves and could not afford to leave and many were suffering of Alzheimer’s disease, the aftermath of a stroke or another debilitating condition.

He and his cohorts began to dream of a place where seniors could remain in their own neighborhood and, not only have basic needs met, but thrive in a community. Project SAVE evolved into Bridging Communities Inc. and went about raising funds for a senior apartment complex.

“We got a number of religious leaders on board,” he remembers, and the core group of about seven began raising funds, work that lasted 13 years. Davis never got paid a dime for his time, but once the name of the facility was unveiled — the Pablo Davis Elder Center — he joked that his deferred salary was really just a backdoor naming-rights fee.

Davis keeps an apartment at the center, of which he is clearly—and rightfully—proud. Having personally sat through many a meeting in its community room, I am pretty familiar with the large windows that offer views of cheery patios and the green expanse of Patton Park, the comfortable lobby and the very proper C. Patrick Babcock Library, filled with books and of course, art. It turns out that the slice of land the Elder Center sits on was once pegged for other uses ranging from a correctional facility to a 7-11, and Davis credits Babcock, who headed up the state’s Department of Social Services back in the late 1980s, with helping push the project through.

The Elder Center was completed in 1998, but Davis sees his work as being far from complete. He and Bridging Communities are forging ahead on what he sees as the core component of his project: an intergenerational center attached to the Elder Center. Citing existent “age segregation” as a negative that this center would try to correct, he envisions a place where home-bound elderly will spend a few hours a day with children at daycare, an interaction that would be of benefit to both groups. His ultimate goal is for the intergenerational center to be “built with the ideas of community and equality.”

The Elder Center was completed in 1998, but Davis sees his work as being far from complete. He and Bridging Communities are forging ahead on what he sees as the core component of his project: an intergenerational center attached to the Elder Center. Citing existent “age segregation” as a negative that this center would try to correct, he envisions a place where home-bound elderly will spend a few hours a day with children at daycare, an interaction that would be of benefit to both groups. His ultimate goal is for the intergenerational center to be “built with the ideas of community and equality.”

With decades behind him and years and canvases and construction ahead, Davis is a busy man. And while certainly not one to rest on his laurels, neither is he one to disavow accomplishment. He muses, “I love it. We successfully built a substantial housing development that feels like home. That’s what I wanted.”

Madonna University and Wayne State University have collaborated on a film biography of Davis, which will premiere at Madonna on December 15. The following day, Emery King’s WDIV series, “World Class Detroiters” will focus on Davis. Read more about Davis at his web site, www.pablodavis.com.

Kelli B. Kavanaugh is development news editor for Model D.

Photos:

Pablo Davis

Rivera Mural at the Detroit Institute of Arts

Pablo Davis

The Pablo Davis Elder Center

All Photographs Copyright Dave Krieger