How a surprising partnership will result in internet for Detroiters lacking access

Called the Equitable Internet Initiative, the project will provide internet to 150 Detroit households and was made possible by a partnership of organizations with different strengths and missions, coming together for a common cause.

Meghan Sobocienski remembers a recent summer day when the internet at the church Grace in Action was down—again. Members of the youth-run collective Radical Productions, which does web development and is housed in the church, had to halt their activities for the day while they waited five hours for a technician to arrive and troubleshoot the connection.

“Would that ever happen downtown?” asks Sobocienski, who is the cofounder of the Southwest Detroit church. “If that happened to G.M. and their internet was down for five hours, would they and say, ‘Stop working, go home’? No. But it happens all the time in the neighborhoods.”

This wasn’t the first time that the internet went down at Grace in Action and they couldn’t fix it themselves. But it might be the last.

That’s because the church is going to be the hub of a powerful Wi-Fi connection that will provide 50 nearby households with high-speed internet. Two other hubs, located in the North End and Islandview neighborhoods, will be the base of routers and another 50 households each.

Called the Equitable Internet Initiative (EII), the project was made possible through new infrastructure provided by Rocket Fiber, a cutting-edge internet service provider headquartered downtown, and largely financed by the New Economy Initiative (NEI), a business development organization with foundation support. The project was designed and implemented by the Detroit Community Technology Project, a sponsored project of Allied Media Projects (AMP).

Each brought something unique and essential to the table. And the partnership demonstrates the potential to enact change when nonprofits, corporations, and foundations join forces.

Detroit’s digital divide

The story of Grace in Action’s temporary loss of internet is endemic of a much larger problem in Detroit: complete lack of internet. Many Detroiters can’t afford it, have to prioritize other more basic needs in their homes, or can only get slow, unreliable internet service and have decided to opt-out. As of 2015, over 60 percent of low-income Detroiters lacked broadband in their home.

This state of affairs is hurting Detroiters’ job prospects, educational attainment, ability to stay informed, and in turn, causing even greater inequality.

“What does it mean when our city has access to the fastest internet in the world, but most its residents are on a really slow connection?” says Diana Nucera, AMP’s director of the Detroit Community Technology Project. “What I fear the most is a digital class system that arises because some people have access to much more information, while others are still trying to catch up. My job is to even out that playing field.”

AMP has been working on bridging the digital divide for years. In 2010, it was awarded $1.2 million in funding from the Broadband Technology Opportunities Program (BTOP) federal grant. From that came the Digital Stewards Training program, which trains neighborhood residents in skills like community organizing and wireless hardware installation. The program trained over 25 stewards and installed mesh networks, where data is distributed amongst nodes, in seven communities.

BTOP funding eventually dried up. But the stewards, curriculum, and community connections remained—the project just needed institutional partners to further their mission. That’s when negotiations with Rocket Fiber began.

The internet service provider has deployed fiber optic cables to large parts of the greater downtown area—Midtown, Woodbridge, and parts of Corktown and the East Riverfront—to deliver some of the fastest internet in the country. It’s a technology with an “unlimited potential,” according to Rocket Fiber CEO Marc Hudson. “It’s a future-proof technology. You install it, and as you upgrade over time, you can continue adding bandwidth. … From now until as far as anyone can see, fiber optics will be the backbone of the internet.”

Rocket Fiber decided it wanted to expand the kinds of services it offers and to whom it offers them. But given how expensive it is to lay down fiber optic cables, versus copper-based technologies like DSL and traditional cable, it had to try something different to reach residents outside the 7.2 miles of greater downtown.

“Rocket Fiber has had ambitions to grow elsewhere and be a part of digital inclusion in city of Detroit,” says Hudson. “We knew other groups were working on these issues, so we stepped back before saying we wanted to solve the city’s connectivity problems ourselves. That’s when we were connected with Allied Media. … We were intrigued by their model thought they had a lot to teach us.”

So in collaboration with AMP, Rocket Fiber built wireless infrastructure to beam 1 gigabit per second connections to routers in neighborhood hubs. It will be selling the internet at wholesale prices. The whole initiative is being supported for at least two years by a $200,000 grant from NEI, with additional support from the Ford Foundation, the Open Society Foundations, and the Knight Foundation. (By comparison, a gigabit internet package from Xfinity in Southwest Detroit costs $139.95 per month and is not symmetrical, meaning the maximum upload speed is only 35 Mbps.)

Getting the project online

After a two-year incubation period, the initiative is finally underway.

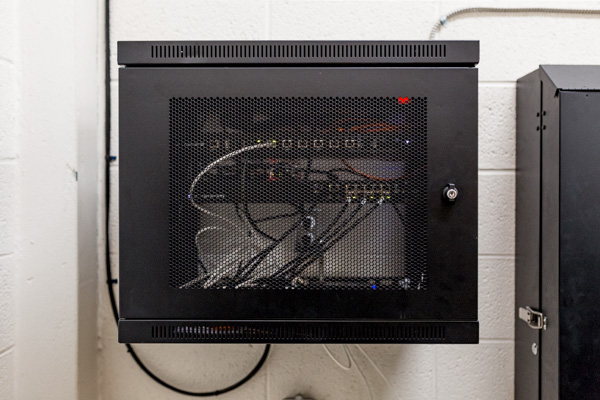

Routers have been installed in neighborhood community hubs: Grace in Action in Southwest Detroit, WNUC 96.7 community radio station in the North End, and Church of the Messiah in Islandview.

Another important pillar of the plan is that the digital stewards are all residents in their own community, familiar with the geography and people, and the best possible representatives for the initiative.

“Our decisions are based on what the community is telling us because we’re entrenched,” says says Monique Tate, a digital steward trainer in the North End. “And by residents being literal participants and initiators in the project, we gain huge amounts of credibility.”

Digital steward trainers have assembled teams of five, which received their own training on-site and at the AMP offices. Community surveys—to map out the neighborhoods and do community outreach—began in late July. The goal is to have wireless internet installed in all 150 homes by mid-October.

But there’s a lot of work to be done until then. For one, the teams need to decide which households will get internet access. Tate says they’ll be selected based on a range of criteria, such as whether a home has low to no internet (10 Mbps or less), children, seniors, anyone pursuing educational opportunities, and where the routers can make the most impact (in an apartment building with multiple families or a neighborhood gathering space).

The routers will have other features in which connected households need to be trained. All computers on the network, for example, will have access to an internal intranet that will allow for secure communication even if the internet is down.

The connection will also be used as an education and skill-building platform for neighborhood youth. Called the NextGen Apps program, 20 students will receive a free, four-week training in app development and coding. Six graduates will then take part in an intensive training to prototype applications designed specifically for these neighborhood connections.

Because funding won’t cover the connections in perpetuity, each anchor organization and the teams of digital stewards have to develop business models that allow for long-term financial and technological sustainability.

And the plans have to be affordable, according to Jenny Lee, executive director of AMP. “They’re really faced with hard questions. How do we do this in way that doesn’t replicate the inequities of other utility companies? Are we going to be the equivalent of water department coming to shut you off if you don’t pay your bill?”

Tate says the key to getting resident opt-in is to give them a sense of ownership. “Your parents may have given you your first bicycle, but when you buy your own, you had much more appreciation and respect for it,” she says. “We need to make people feel like it’s theirs, then they’ll be compelled to want to take care of it.”

There are models already being considered, but whatever is chosen, it will ultimately be up to the neighborhoods themselves. This internet is theirs, says Nucera. “These folks will be the ones organizing, building the infrastructure, and teaching others, hopefully to create a culture of collective ownership.”

This article is part of “Detroit Innovation,” a series highlighting community-led projects that are improving the vitality of neighborhoods in Detroit, while recognizing the potential of residents to work with partners to solve the most pressing challenges facing their communities.

The series is supported by the New Economy Initiative, a project of the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan that’s working to create an inclusive, innovative regional culture.

All photos, except where mentioned, by Nick Hagen.