Why Detroit’s independent bookstores matter — and have been steadily growing

Beginning with Source Booksellers, which opened in Midtown in 2002, the city has seen a slow but steady rise in independent bookstores. And they've survived largely because of their importance to local residents.

Every year on the last Saturday in April, indie bookstores get to celebrate what truly makes them special—their independence.

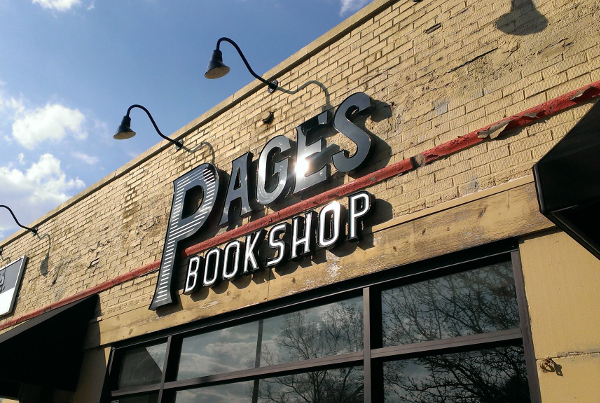

This April 28 at 11 a.m. sharp, customers were already waiting outside of Pages Bookshop in Grandmont Rosedale ready to take part in Independent Bookstore Day, a national yearly celebration of local bookstores. Into the early afternoon, the bookstore was still packed with book lovers, some solely focused on browsing the tables and shelves, while others casually wandered through the store, complimentary mimosa in hand, chatting with other customers or sitting down and reading their new purchase.

This casual community atmosphere is what defines the local, independent bookstore. Beginning with Source Booksellers, which opened in Midtown in 2002, the city has seen a slow but steady rise in independent bookstores selling mostly new books. Pages followed in 2015. Another, Book Suey, recently opened in Hamtramck.

Contrary to what the bookstore’s well-stocked shelves and pleasant atmosphere might lead you to believe, however, owning and operating a bookstore is a risky venture.

The elephant in the room is, of course, Amazon. Since the online retailer’s inception in 1995—coincidentally the same year the American Booksellers Association (ABA) reported a historical high of independent bookstores in the U.S.—bookstores have struggled to stay afloat. By 2000 almost half had gone out of business.

But surprisingly, by the end of the decade, that trend had started to slowly reverse. In 2009, the ABA reported a 35 percent increase in bookstores throughout the U.S. Today the ABA says there are 2,321 independent stores nationwide—a number that is still trending upward, suggesting that indie bookstores are much better poised to survive in the era of Amazon.

But just because indie bookstores are still around, that doesn’t mean their existence should be taken for granted. On days that are not Independent Bookstore Day, many still struggle to keep their doors open.

“You can’t stop people from buying online or buying at Walmart,” concedes Oren Teicher, CEO of the ABA.

He’s been in the business long enough to know. “It’s important [for consumers] to remember that if you value the bookstore in your local community, but if you don’t buy some books from them every once in a while, they can’t survive.”

Although it might not seem like it at the time, when you decide to pay the extra five or 10 dollars for a book at a bookshop, you aren’t just deciding the fate of the store, but you are also the future of your community. “Customers vote with their money,” Susan Murphy, owner of Pages Bookshop, says. “If you want a community that has a bookstore, you need to support it because if you don’t, it’s going to go away.”

And there are a lot of reasons Detroit and other urban communities should want to keep their independent bookstores around. At a time when face-to-face interactions are becoming less common, independent bookstores act as a kind of community center. They hear first-hand from their customers what is important to the community and respond through book curation, author visits, and community partnerships.

In his recent study on independent bookstore business, Harvard Business Professor Ryan Raffaelli found that independent bookstores have become even more valuable in today’s world where so much of an individual’s free time can be spent online. “People are still eager to connect, and indie bookstores make that happen,” Raffaelli says. “They create a safe space for individuals to debate new and important ideas with friends and neighbors.”

Janet Webster Jones, owner Source Booksellers, agrees. “[Raffali] had to learn what most of us already knew: Bookstores provide a place where people can convene,” she says. “Human beings want their stuff, but they also want relationships.”

Source’s design reflects this. From the non-fiction books that Source exclusively sells, to the yellow chair tucked in the corner to the wooden table in the back, everything in Jones’ store is thoughtfully curated in a way that makes you feel at ease. You want to stay awhile. It is a great example of how a bookstore invites people to drop their guard and open themselves up to different ideas and opinions.

“A comfortable place to explore” is how Murphy describes her bookshop. Depending on when you walk in, you might find her suggesting a book to a new customer, conversing with a local about what was in the news that week, or catching up with one of her neighborhood regulars.

Browsing a bookstore might not be as quick or convenient as an Amazon search, but true human interactions and connections rarely are. Both Jones and Murphy know they can’t compete with Amazon in price or selection, so they aren’t even trying. Instead, they, like other independent bookstores, are trying to be cultural anchor points in their community.

“A bookstore that is embedded into a community understands its customers and tailors its selections to them,” explains Murphy. “When customers come in, [the books] reflect who they are, what they are, and what the neighborhood is all about.”

In an age when it’s so easy to become isolated and hide behind a screen, going to a bookstore—whether it’s to pick up a new book or attend an event—seems to be more important than ever before.

“Bookstores will be around as long as humans want them,” Webster Jones says.

Going off the attendance of this year’s Independent Bookstore Day in Detroit, it looks like they might be around for a while.

Disclosure: Erin Gold works part-time at Pages Bookshop.

Photos of Source Booksellers by Marvin Shaouni.