Mr. Mies’ neighborhood

New book contains insightful essays, interviews with current and former residents, arresting portrait photography by local photographers, as well as an abundance of historic images, says our high rise specialist, Matt Piper.

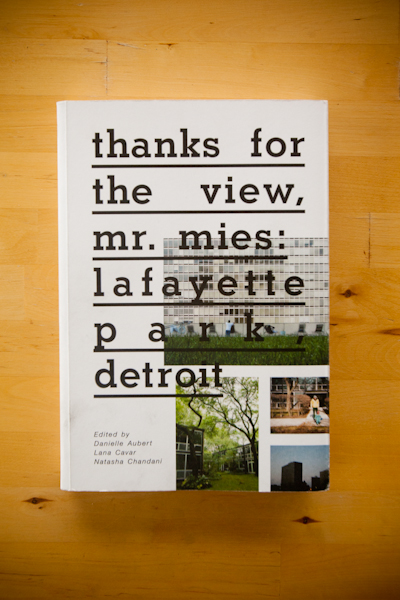

If you’re unfamiliar with Detroit’s Lafayette Park, the singular, mid-century modern neighborhood just east of Greektown, you’re not alone. Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies: Lafayette Park, Detroit, an indispensable new book about what it means to live there, includes an elegant essay by resident Marsha Music in which she describes the neighborhood as “hidden in plain sight.”

That’s partly a nod to the abundant glass that helps define the architecture of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. He designed 162 rectilinear, two-story townhouses, 24 one-story courthouses, and three high rises built there between 1958 and 1963, all of which feature his trademark window walls. From Lafayette Blvd., it’s easy to overlook the glass, brick, and steel houses, nestled unassumingly in mature greenery. Even the soaring, skeletal, 21 and 22 story high rises can be pretty inconspicuous, thanks to the subsequent proliferation of the International Style. (Minimalist glass towers may still catch the watchful eyes of architecture buffs, but the years have somewhat dulled the striking, “Behold: The Future!” quality they once possessed.)

Music’s phrase is also a reference to Lafayette Park’s relatively low profile in architectural and design circles worldwide. Though it isn’t mentioned much, much about the development is notable. There are Mies’ buildings, of course, the largest single collection in the world (take that, Lakeshore Drive!). Then there’s the work by the other members of the design dream team who were brought to Detroit from IIT in Chicago to execute the park: planner Ludwig Hilberseimer, who oriented the entire development around the 19-acre, prairie style Lafayette Plaisance, and landscape architect Alfred Caldwell, whose contributions, including the park, have grown over the years into a lush, “absurdly bucolic” urban environment. Lafayette Park is, in fact, the most fully realized “settlement unit” mutually envisioned by these three designer-philosophers in the world.

There’s also the fact that, depending on who tells it, Lafayette Park is either one of the only successful urban renewal projects in the county, or the sole example. It was intended to keep the middle class in the city, and for one neighborhood, anyway, it did (at the terrible expense, it should never be forgotten, of Black Bottom, the densely populated black neighborhood that was razed to make room for it). It also realizes a great dream of modernism: in addition to being racially integrated from the very beginning, the houses have remained affordable for middle class buyers for decades. The rental apartments, meanwhile, are a steal, giving working-class people and young professionals the opportunity to live in buildings whose pedigree — not to mention floor to ceiling windows — would make them off-limits in any other city. (Except maybe Newark.) I’ve been a high rise resident for more than four years, and I still sometimes feel like the Mies Police are going to show up any day now, check my tax bracket, and tell me to start packing.

Thanks for the View’s three editors, graphic designers Danielle Aubert, Lana Cavar, and Natasha Chandani, who met in grad school at Yale, call themselves Placement: they’re “interested in the ways that places are represented and experienced.” They became interested in Lafayette Park when Aubert moved there and began wondering why Mies “is not as well known for the buildings he made for middle- and working-class people” as he is for his upscale developments. Attracted by the fact that the neighborhood’s appeal has “as much, if not more, to do with its long-standing multigenerational, racially mixed, economically stable, tight-knit community as it does with the architecture,” they spent three years seeking to understand the neighborhood from the inside out.

The result is their first book, an exuberant thing brimming with insightful essays by and frequently very funny interviews with current and former residents, arresting portrait photography by local photographers Corine Vermeulen and Vasco Roma, as well as an abundance of historic images, neighborhood ephemera, promotional materials old and new, and snapshots taken by residents over the years. There are also a number of unexpected and endearing digressions, including a section called “Celebrities Rumored to Have Lived in Lafayette Park” (Carl Craig, yes; Madonna, no), “Authentic and Original,” a partial inventory of 38 original townhouse fixtures (including the drop-down Frigidaire cooktop), and “Birds and Plate Glass,” a sober photo series documenting what happens when unfortunate birds come into high-speed contact with Mies’s glass walls.

Aubert, Cavar, and Chandani obviously care about the architecture in Lafayette Park, but like many residents of the neighborhood, they don’t worship at the temple of Mies, and that’s refreshing. Frustrations of daily living are honestly represented: one section is titled “A Record of Nine Days Spent Keeping the Climate Under Control in a Corner Apartment.” Elsewhere, a townhouse resident longs for “a real-sized kitchen” that’s not “so claustrophobic.” A resident of the Pavilion, the 21 story high rise, wishes for a dishwasher, whose absence “kills (his) motivation” to cook. These point to an essential quality of this expansive and good-natured book, in which individual personalities shine: it is fundamentally descriptive, not prescriptive. It is more interested in realism than idealism, or, perhaps more accurately, in what happens when real people inhabit idealized spaces over time. There is no finger wagging at the apartment residents who’ve never heard of Mies (“Is he a good architect?”), only an earnest desire to understand each one’s individual experiences and represent them as a true part of life in an extraordinary place.

Architecture and design enthusiasts looking for chewy tidbits will find them, especially in essays by residents Noah Resnick and Melissa Dittmer, and an interview with Neal McEachern, who all engagingly illuminate different aspects of the rowhouse and landscape design, as well as life lived “on display” in glass houses. Marsha Music, in her previously mentioned essay, offers a remarkably personal history of the development, and performs a poignant resurrection of the buried spirits of old Black Bottom that has, I suspect, forever changed the way I will think about the neighborhood.

Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies is an exciting addition to a too-scant body of literature. It was preceded in 2004 by CASE: Lafayette Park, a Harvard Design School critical study. That previous volume is still the best place to turn to for a sustained, scholarly analysis of the neighborhood, but in contrast to the largely specialist audience for which it was clearly intended, I’d be hard-pressed to find anyone I wouldn’t recommend Thanks for the View to. Throughout it, Aubert, Cavar, and Chandani’s hands are sure but light. Their editorial contributions are plainspoken, direct, and accessible, and like Mies’s windows, they provide simple, clear frames through which to see life, in its marvelous and idiosyncratic variety, enacted.

Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies: Lafayette Park Detroit will be available starting tomorrow, Oct. 17, at the Source Booksellers, 4201 Cass Ave. A book launch party at Signal-Return (1345 Division St.) is Oct. 17 (that’s tomorrow night), 6-9 p.m. On Thursday, Oct. 18, at 7 p.m., the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (4454 Woodward) will host a panel discussion between the editors, Marsha Music, and Joe Posch, moderated by Robert Fishman. Finally, there will be author readings at Book Beat in Oak Park at 2 p.m. Sunday, Oct. 21. Book Beat is at 26010 Greenfield Rd.