Q&A: New book by Detroit essayist Rochelle Riley enlivens Black history for young readers

Model D recently talked with Riley about the making of this unique children’s book, her artistic role with the city and own creative projects, thoughts about Black History Month in America, and what’s bringing her hope amid a challenging new year.

It was four years ago this month when Rochelle Riley, director of arts and culture for the city of Detroit, lost her heart on Twitter. The young girl who stole it couldn’t possibly have known the triumph and struggle her eyes reflected. They peered from the screen daily, out of black and white photographs of women Riley had long revered. Trailblazers she’d learned about in school, celebrated with family, even strived to emulate through her own career. It was uncanny how closely the girl captured her heroes and lifted them straight off history book pages.

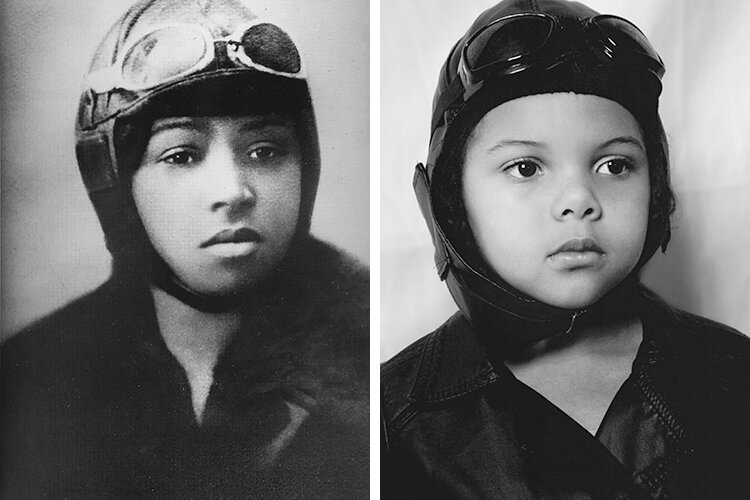

Delighted, Riley reached out over social media to meet the young girl’s mother and photographer, Cristi Smith-Jones, who lives with her family outside Seattle. The portraits she and her daughter Lola meticulously recreated were part of their own study and celebration of Black History Month, 2017. Riley asked if she could collaborate with the pair by writing biographies to complement their photos. She hoped to pen a history that would engage young readers the way Lola’s youth would surely capture their curiosity. The newly released book, “That They Lived,” is a result of that collaboration. It brings to life 20 historic figures, in then-and-now fashion, reminding readers that those who achieve greatness have all been children first.

Model D recently talked with Riley about making this unique children’s book, about her artistic role with the city, her own creative projects, her thoughts about Black History Month in America, and what’s bringing her hope in a challenging new year.

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Model D: Tell me what was special about the photographs of Lola you saw on Twitter in 2017, and how they inspired you to make this book?

Rochelle Riley: Little Lola stole my heart. The way she captured how these women looked, it wasn’t just dress-up, though she was 4 when she started, then 5 and 6. They were detailed recreations— from Fannie Lou Hamer’s photo, where she’d been beaten up in the jail and had the bruised eye, to Barbara Jordan’s profile with her hands clasped, to Katherine Johnson with the glasses and the dress. I thought, these are amazing. I reached out to the woman who’d posted them to tell her I loved them. It was nice, just strangers meeting on social media, but then, I couldn’t get the photos out of my head.

I sent her [Smith-Jones] a note asking to take what she was doing, which was so important, a step further. I wanted to write the biographies of these women so people would know their backgrounds and what famous people were doing as children. Each essay says, When this person was 11 years old, she was doing this, and she became this. I wanted 11-, 12-, and 13-year-olds to read this and go, They were my age! So whatever they’re doing at my age, and they became this, I can become whatever I want to be. The goal was to make every kid, their parents, their grandparents and teachers remember every important person was once a child.

Model D: What made you expand Lola and her mom’s idea to include African American men of history, portrayed by your grandson?

Riley: People who know me know I always think big. I told Cristi we could do one book focused on women, then one for scientists, businessmen, sport stars, etc. But she only wanted to do this book. So I said, then we can’t leave out young boys. Our boys are under siege, and they need to be lifted up and inspired as much as girls. My [then] 9-yr-old grandson [Caleb] and I flew from Dallas to Seattle for a three-day photo shoot. The only thing I brought was his black suit because we needed one for Martin Luther King Jr., and everything else Cristi found at thrift and hair/makeup stores. My grandson’s favorite photo was Frederick Douglass because of the hair. (laughing) He wanted to go to the movies with that hair.

Model D: Working with children to portray adults, how did you and Smith-Jones keep the project representative rather than cutesy?

Riley: I think a big thing was that very few of these pictures had people smiling. Cristi did the setup, the lighting and detailed costumes. She took all the photos. I wanted to add the essays because I wanted them to be more than posters. Every Black History Month, we throw out names of Black people who did things and celebrate them. I wanted people to know the backstories of these folks. These are not hidden figures, these are people that every child of every race should know and aren’t always taught in school. We’ve had a terrible problem with miseducation in this country for years. We haven’t told the stories of African Americans, particularly those who helped create America, which is why it’s so easy to think that Black people aren’t as important or haven’t achieved as much. We have to do better. I want to change the narrative.

Model D: I read that Cristi and Lola’s project was inspired when Lola came home from kindergarten to say she’d learned about Dr. King. I’m wondering what African Americans you remember learning about in school and how you connected with the history you were taught?

Riley: My elementary years, at least until sixth grade, were spent in a segregated school in a little town called Tarboro, North Carolina. My first and second grade teacher was my grandmother’s first cousin, so my experience as a student was different from what went on on the white side of town, where there was no teaching of Black history. We learned about people like George Washington Carver and Dr. King, and it wasn’t just in February. Our teachers found ways to make sure we knew about things as they happened, whether it was about famous writers, actors and actresses, scientists or politicians. In my household, there was a true understanding of history. My father was a chemistry professor, my mother was an english professor, so for us, it wasn’t a revelation. We didn’t go to school and say, who was he? I probably knew about Black politicians 10 years before some of my white colleagues when we finally went to integrated schools. But so much of my early years resonate, like most people of my generation, with King.

Model D: Having been taught Black history as American history, how do you feel about Black History Month?

Riley: I wrote a column, maybe 10 years ago, saying that we should abolish Black History Month. People lost their minds. They wanted to set their hair on fire because they read the headline and didn’t read the column. What I said was, we need to teach all of American history all year, and by relegating the teaching of Black history to one month, and treating people like posters, we were doing a disservice to the whole of American history. Once people actually read the column or talked about it, they got a little better sense of it. But you know, Carter G. Woodson fought so hard for the recognition of Negro History Week, and then Black History Month, that nobody wanted to give that up. And I now understand that. I still fight against the idea that we only talk about these people, or study this struggle and the things that happened, in February. I continue my Black history studies through March, April, and May, but I no longer think we can afford to give it up, because giving it up means people just won’t study it at all.

Model D: With such a passion for education, are you hoping your book will be used in schools?

Riley: I want this book in the hands of every kid in every school in America, not just Black kids. I think part of the reason we have such racial conflict is because we’ve never dealt with the full stories of any race except white Americans. Just imagine what Black kids would feel like if they knew the story of the struggle that Black Americans went through to get to the point where they were achieving. If they knew that Thurgood Marshall won more cases before the Supreme Court than any other attorney, of any color. You know, those are the types of things that, if they’re a part of your knowledge base, you don’t look at a Black person and automatically think what you know about them is that their people were once enslaved and they’re probably not as smart as you are, which is the myth that’s persisted because our country’s allowed that.

Model D: What are some of the fun and surprising facts you learned about these historical heroes while writing this book?

Riley: Oh, my god, there’s so much. For instance, I didn’t know that Duke Ellington manned a counter at a soda fountain and wrote his first composition, “Soda Fountain Rag” when he was 15 years old, before he learned to read or write music. Go on brother! I just didn’t realize how early he got started. Or Bessie Coleman, the first and most famous African American aviator in history, worked in cotton fields with her family when she was young. She had a great love of math, and later when she read about French women flying, she said, I’m going to do that. People laughed at her, but she went to France to learn. Ida B. Wells, who was my hero, and this amazing journalist that people adore and emulate, she had to raise her family because she lost her parents and a brother to yellow fever. She raised seven children at 16 years old!

I reveled in the idea of readers understanding what happened to these people in their childhoods. You never know what moment in your life might change the trajectory of your life. Jackie Robinson! Everyone knows what he accomplished by integrating Major League Baseball, but when he was 16 years old, he was a member of a gang. Look at where these people were, and then what they were able to accomplish. You just never know what your future is. Stevie Wonder was a genius at 11 years old, and his mother knew that. You’ve got to have somebody in your corner who sees something special happening. You might be the person to see it, or somebody might see it in you.

Model D: You edited “The Burden,” a powerful collection of essays released in 2020, that explores the impact of slavery on generations of African Americans. What was it like to pivot from that book to one that cries, we’re more than descendents of slaves?

Riley: “The Burden” came about because a columnist wrote that African Americans needed to get over slavery, and they were better off in America than they were in Africa. It was just a horrible, awful, misguided thing. I wrote a Facebook post about it, and the response was so amazing, I thought, I have to do something bigger. If I create a chorus of voices to help explain to people why enslavement continues to harm African Americans and continues to affect how we live, then nobody would feel or see things the way this guy did.

After “The Burden,” I started thinking that part of the reason people don’t understand how sometimes horrible it is to be African American, is because they don’t know how horrible it feels to have done so much, and excelled at so much, in spite of so many obstacles. We went from a people that America made it illegal to teach to read, to being exceptional in every way. And that’s sort of hidden or tamped down, that we’ve been equal all along. And we’ve been fighting for equality all along.

I could write an entire set of encyclopedia with folks like this, African Americans who have excelled in many ways, and maybe I’ll still do that. So there’s a whole grouping of these books where people can see all the ways we’ve excelled in spite of—which means of course, we’re twice as good, which our parents taught us to be.

Model D: This is not the first project you’ve done with photographs over the past year. Last summer, you planned a Memorial Drive on Belle Isle to honor 1,500 Detroiters who lost their lives to COVID-19. The homegoing featured over 900 photo billboards.

I’m thinking about the title of this book, “That They Lived,” and the use again, though in a much smaller way, of photographs. What is it about visual art that moves people?

Riley: I’m so glad you asked that. I’ve always been a creative spirit and a visual person. I write because it was a way to make a living doing something I love, but I also paint and take photographs and hope to someday make a film. Sometimes, to make people understand something, you have to show them rather than tell them, which is why I’ve always loved the idea of working with photographers to accompany things I write. Sometimes 1,000 words will do it, and sometimes a photo does something 1,000 words can’t. The idea for the [Belle Isle Memorial] pictures — and it’s amazing you asked that because it was to prove that they lived. At that point, there were 1,500 people who were snatched from us, and there was never a chance to say goodbye. It’s not enough to have a eulogy or to say something, I wanted people to see them. I can’t get away from this idea that we’re not dealing with this massive loss that’s going on. At some point, we have to reckon with that. So every time we lose someone, I want people to remember that they lived.

Model D: Each person featured in your book overcame obstacles in their life through determination and perseverance. Detroiters, young readers included, are facing many obstacles right now amid COVID-19 and the continued fight to end systematic racism. Despite these obstacles, what is giving you hope in 2021?

Riley: I firmly, firmly believe, for the sake of my family, and the sake of children across this country, that people will finally come to realize we can no longer live like this. George Floyd sacrificed his life — not voluntarily — for people to finally see and hear what African American citizens have been trying to tell the world for years. I think people finally hear us. I think they see us. I think there was a shift felt globally that might make a difference. But what gave me the most hope was seeing those protests around the world. Around the world, because of this incident. It took this one incident to finally wake people up. I hope we continue to take advantage of that. I think the reason Joe Biden was elected, was not because he was Joe Biden, but because Donald Trump was Donald Trump. We’re in a different place now, and that gives me hope.

Rochelle Riley’s first of many virtual author talks for families on “That They Lived” will be held at Source Booksellers on Sat. Feb. 6 from 2-3 p.m.

Free event tickets and book purchases can be made at Eventbrite.