International Style

Downtowns are sharing strategies on how to revitalize local economies. One expert says by getting a little help from friends around the world, Detroit is poised to star again on the international stage.

America’s Midwestern cities feel so depressed sometimes. But they aren’t alone in the uphill battle to bring people back together downtown. In fact, there are hundreds of cities across the globe struggling to revitalize inner-city marketplaces. From Chiyoda-ku in Tokyo, Japan to Brisbane, Australia; from lower downtown Manhattan to Prague, Mexico City and even Windsor, Ontario, cities are scrambling to capitalize on the last decade of urban growth by generating new businesses, public spaces and visitors.

But it’s not easy.

With similar challenges, some 650 cities belong to a support group dubbed the International Downtown Association (IDA), through which they can get expert advice on all sorts of ways to pump life into struggling inner cities. Founded in 1954, around the time when downtowns were beginning to hemorrhage residents, jobs and stores, the IDA has members in North America, Europe, Asia and Africa.

With similar challenges, some 650 cities belong to a support group dubbed the International Downtown Association (IDA), through which they can get expert advice on all sorts of ways to pump life into struggling inner cities. Founded in 1954, around the time when downtowns were beginning to hemorrhage residents, jobs and stores, the IDA has members in North America, Europe, Asia and Africa.

Hope amid struggle

The head of the IDA, David Feehan, spent time at downtown organizations in Detroit, Kalamazoo and Pittsburgh before taking his seat as president of the international organization. The cities where he cut his teeth have progressed much during and since Feehan’s tenure.

Kalamazoo is in the top 10 percent of cities its size in terms of downtowns, Feehan says, and in December, Pittsburgh was named the IDA’s “downtown of the month” for its recent progress, including a surge in residential development downtown. And Detroit is closer than ever to getting back on its feet, Feehan says, thanks to the work of people like Matt Cullen, general manager of the Economic Development and Enterprise Services group for General Motors, and Roger Penske of the Downtown Detroit Partnership (a group that was formed, in part, out of the Greater Downtown Partnership, which Feehan founded).

“Finally, Detroit, I think, over the next 10 years will take its place as it should among great American cities,” Feehan says.

“Finally, Detroit, I think, over the next 10 years will take its place as it should among great American cities,” Feehan says.

While so many inner city problems seem specific, there are many similarities among downtowns internationally, Feehan says. For instance, so many Americans think Paris is an urban paradise, but it’s got its own problems.

“You can look to cities across the globe for signs of hope and similar problems, “Feehan says. “In Paris, the poor folks and the immigrants are largely shoveled to the suburbs where business districts are the most vulnerable. The European cities are looking to the United States to figure out how we deal with integration.

“In Paris, if you take the metro and ride around, you’ll see that the city is struggling with a lot of the issues of U. S. cities. You’ll see a fair amount of trash and litter and graffiti,’ he says. “A lot of American cities have really taken on the graffiti problem and have done a good job to eradicate it. If you deal with graffiti, you deal with the image problem.”

Detroit, Pittsburgh and Grand Rapids can look to South Africa’s Johannesburg for inspiration in terms of a metropolis that is cosmopolitan and racially-mixed despite a turbulent history. People joke that Detroit is the victim of a racial war, but Johannesburg actually was the site of a race war. Today, black and white visitors mix commonly in Johannesburg’s museums, cafes and downtown gathering spaces.

Immediately after apartheid was dismantled, the city leaders got together to protect and grow the inner city using “business improvement districts,” Feehan says. It worked.

“The securing of downtown as a public place, a place where people of all races can go, has had a significant psychological effect on the city and the whole country. It’s a surprisingly cosmopolitan place to be,” he says.

“The securing of downtown as a public place, a place where people of all races can go, has had a significant psychological effect on the city and the whole country. It’s a surprisingly cosmopolitan place to be,” he says.

Johannesburg created an incubator for the fashion industry, and now there are young South African designers getting work shown in international fashion magazines.

“There’s a lot of talent in a place like Johannesburg,” Feehan says. “It’s a matter of giving people hope and saying, `You can play on the world stage.’ Just because you’re from Africa doesn’t mean you can’t play on the world stage.

“I think there’s a lot of that in Detroit, a feeling that, `We’re not good enough and can’t do anything right.”

Creating a vibrant, interracial downtown can help a city get over that feeling, he says.

Success breeds success

While it’s difficult, clearly, to create something new out of downtowns that are old, there is a road map, so to speak, culled from years of successes and failures. There are tried and true methods to make things happen.

“It’s a very good time for downtowns,” Feehan says. “We’ve now had about 10 to 15 years of success. We’ve finally figured out how to do it. During the 1960s through the 1980s, we spent a lot of money trying to redevelop downtowns using silver bullets like aquariums and stadiums. What we finally figured out is that, first and foremost, downtowns must be clean, safe, friendly and attractive.”

“It’s a very good time for downtowns,” Feehan says. “We’ve now had about 10 to 15 years of success. We’ve finally figured out how to do it. During the 1960s through the 1980s, we spent a lot of money trying to redevelop downtowns using silver bullets like aquariums and stadiums. What we finally figured out is that, first and foremost, downtowns must be clean, safe, friendly and attractive.”

Member cities in the International Downtown Association use the group for panel discussions, in which experts go to that city, meet with leaders and try to come up with solutions and plans. Of course, it takes money and commitment from private sector and government leaders, and therein lays the challenge.

And it isn’t just struggling cities that use the IDA — Austin, Texas, a favorite hipster enclave, convened an IDA advisory panel in 2004 to get ideas and guidance on how to bring more retail to its downtown. Such panels have been convened in New York City, Washington, Seattle and Los Angeles, among others.

Such successful urban areas might seem to have happened organically — a natural blending of people and commerce — but that’s almost never the case. Most often, money and leadership, in various forms, get together and come up with plans to keep things bustling.

“Downtown associations have proven to be the thing without which nothing would happen,” Feehan says.

Take New York City, for example. Feehan says he recently visited the metropolis and could determine immediately when he was walking in an area with an organized “business improvement district” to an area without such a group.

Take New York City, for example. Feehan says he recently visited the metropolis and could determine immediately when he was walking in an area with an organized “business improvement district” to an area without such a group.

“Around Penn Station, and the Bryant Park area, the streets are really well kept. Then you get to around 34th Street, and the streets look greasy and grimy, there’s graffiti all over the place and there’s nothing planted. Walking from one area to the other was almost like stepping back in time.”

Understanding downtowns

Chicago is the only city Feehan can think of that manages a vibrant, clean downtown without a major downtown association, and he credits the Windy City’s mayors, who “understood downtown and never let it get bad. Chicago has one of the most effective downtown associations in the country. It’s called Mayor Daley, (who is) an incredibly forceful advocate of downtown Chicago.

“Houston, Ft. Worth, Portland, Denver, Seattle, all those cities with great success stories, virtually none of them that could have happened without a strong downtown association.”

Molly Alexander, associate director for the Downtown Austin Alliance, says that despite the city’s great success as an entertainment, restaurant and live music destination, attracting retail has been difficult. The IDA panel was part of Austin’s ongoing effort to recruit shops downtown, she says.

And while it is true that organizations and strategic planning are important, Alexander says she thinks it is a mix of things that make cities successful.

“There are organic pieces of downtowns that occur without anyone doing anything,” Alexander says. She points to the 6th Street area of Austin, where people opened stores because rents were cheap. Her group was founded in 1993 to make sure that the growth of 6th Street and other areas continued.

“Cities don’t grow because you make them grow, they happen because people want things to happen,” Alexander says. “It’s the individual that starts the momentum and then the organization grows around that. I think communities are built form individuals with an entrepreneurial spirit.”

Unfortunately, cities today have much competition, Feehan says.

“The people who built the suburbs and the suburban malls have figured out what people want and they’re giving it to them. Now they’re building downtown centers in the suburbs, and it’s taking the steam out of downtowns in some places,” Feehan says. “City and suburb is the wrong way to look at it. There are a number of downtowns, some newer, some older, some bigger, some smaller that are competing against each other. It’s a question of how to do it the best and the smartest.”

“The people who built the suburbs and the suburban malls have figured out what people want and they’re giving it to them. Now they’re building downtown centers in the suburbs, and it’s taking the steam out of downtowns in some places,” Feehan says. “City and suburb is the wrong way to look at it. There are a number of downtowns, some newer, some older, some bigger, some smaller that are competing against each other. It’s a question of how to do it the best and the smartest.”

Feehan grew up in Minneapolis and moved back and forth from there to Pittsburgh, where he served as president of East Liberty Development, before becoming president of Downtown Kalamazoo Incorporated in 1989.

Fifteen years ago, “the north side of Kalamazoo was becoming a ghost town,” Feehan says. When he arrived, business and government leaders were getting together to try to change things.

“We erased the biggest objection people have to coming downtown, which is parking,” Feehan says. He says he told city leaders to think of the downtown as if it were Nordstrom’s department store. The city began to offer customer services downtown, such as free battery jumps and roadside assistance.

“It was pioneering at the time, there was nothing like it in the country, or in the world probably,” he says. “We had an explosion of success. We transformed Kalamazoo in about 10 years with buy-ins from business, corporations and government.”

Building partnerships

After making strides in Kalamazoo, then-Detroit mayor Dennis Archer brought Feehan to Detroit in 1994 serve as executive director of downtown and community development for Detroit Renaissance. He organized the Greater Downtown Partnership, which bought up the Hudson’s department store property and land around it to make way for Campus Martius Park.

Feehan says Detroit’s Super Bowl preparation was a “remarkable triumph.”

Feehan says Detroit’s Super Bowl preparation was a “remarkable triumph.”

He says he feels better now than ever about Detroit’s shot at a comeback.

“It’s got a brand. Part of the brand is a little negative, but part is good. When you say Las Vegas, you think gambling. When you say Hollywood, you think films. Detroit is one of those cities,” he says. “You automatically think automobiles and Motown. It’s a major U.S. city with an important history in the national and even international economy, and there’s a starting point there.”

Now, he says, the city must “determine where it wants to go and what it wants to be.”

And he offers a warning to downtowns such as Detroit that are working to develop.

“You can’t rest on your laurels in this world. You have to keep three steps ahead of the competition. If downtowns don’t act wisely, they could lose the running start they’ve had in the last 15 years. You can’t sit back, because the competition is too good. [Suburban] shopping center builders are really smart people and they’ve got lots of money. “

Lisa M. Collins is a freelance writer based in New York City. She is a former culture editor for Detroit’s Metro Times and worked as a reporter for the Detroit News.

Photos:

Downtown Detroit

GM’s Renaissance Center and the People Mover

David Feehan, photo courtesy of the International Downtown Association

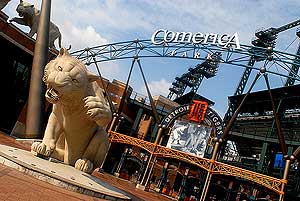

Comerica Park

The Fox Theatre

Comerica Tower

The Elwood Bar and Grill

Compuware

All Detroit Photographs Copyright Dave Krieger